Ian – Latest in a String of Extremes

One of my past supervising editors at the Naples Daily News once said Florida is a state of extremes. The term stuck with me.

STATE OF EXTREMES

Colleen Conant, my boss in the 1990s who came to Naples from Colorado, made the comment in the context of water. Our area either had too much of it, in the form of summer rains, runoff, and flash floods, or not enough of it to wet lawns and golf courses in dry winters, she observed.

The conundrum, if memory serves correctly, helped drive the public conversation about deep-well injection to store rainwater underground until it is needed.

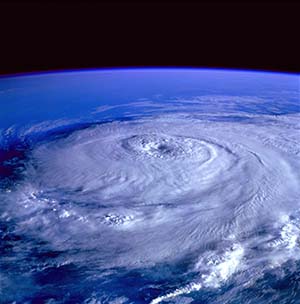

The notion hit home with a vengeance when Hurricane Ian smashed into Southwest Florida. Not only were Ian’s winds extreme, but Ian’s storm surge packed a punch that we had often been warned about but had never seen in such magnitude. Ian’s eye was extremely large.

EXTREME

There was damage to match, tossing boats like toys and carrying cars as if they were boats on streets turned into rivers. There was extreme damage inside homes, out of the public eye.

Even the lack of damage in communities only 10 miles away to the east was extreme, in contrast. Disparities in flooding could be even more close by, where higher, newer subdivisions abut older, lower ones.

Examples abound beyond storms. There are extremes at both ends of the wealth spectrum, as many people enjoy a surplus while others struggle to scrape by. It is no coincidence that statistics for annual income—including dividends and interest—exceed totals for annual wages, with so many low-paying service industry jobs.

An extreme public health situation, the pandemic, sparked an exodus from the North that stressed our already tight and expensive housing market.

There are extremes in population density. Glaring examples are in our own backyard, with Naples and Miami on either side of 1.5 million acres of plant and animal wildlife in the Everglades. Density is a byproduct of development, which can overwhelm one place while a neighboring area yearns for a share.

Development demands workforce, which can be flush in boom times or gone when things go bust. The record shows the construction industry was rescued during the crash of 2008 by three major non-profit projects at the Conservancy, Golisano Children’s Museum, and Naples Botanical Garden.

Local governments’ commitment to infrastructure to keep pace with development can show signs of stress. An extreme example came a few decades ago when, amid a burst of growth, no new roads were built for three full years in Collier County. The result was extreme gridlock at rush hours.

Average temperatures present extremes, either sweltering in summer or too cold for crops in winter. Extreme demand for something as simple as arts and crafts festivals and concerts in downtown Naples has led to calls for a moratorium on new permits.

Our average ages show extreme statistical swings. Collier’s appeal to income tax-conscious retirees shows in our percentage of 65-and-older people, at 33 percent, far outnumbering children, at 4 percent.

Local extremes in ethnic diversity, meanwhile, are lacking.

Voter turnout percentages can swing from lows in the 20s to highs in the 90s.

Extreme politics rears up in data from the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. Florida, with 14 residents charged with violence, ranked second, behind Texas with 15 and New York with 11, according to Forbes Magazine.

EXTREMES

They can be good, too. Consider today’s pace of local performing arts, with at least five major theater launches, expansions, and rebuilds under way. Several are within walking distance of each other downtown, where there used to be none.

An extreme celebration every year is the Naples Winter Wine Festival, which attracts vintners, chefs and philanthropists from around the world for a singular, focused mission—uplifting the education, health and welfare of Collier children. Since 2001 the event has raised $245 million, making it a top festival in the world.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!