Failing in Order to Succeed

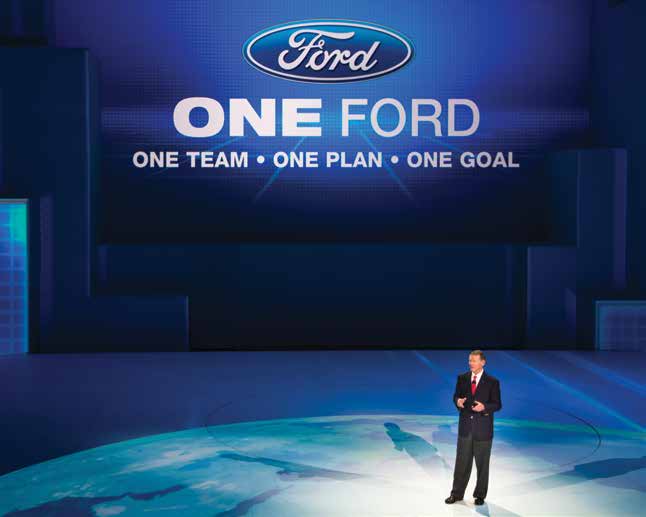

Alan Mulally, CEO of the Ford Motor Company presents at the North American International Auto Show

PHOTO CREDIT INSATIABLEWANDERLUST

Much has been written about “failing”—with the usual drama, sadness, and degree of pessimism about the future course for those involved.

As it turns out, many ordinary people or businesses faced with life-changing or industry-changing events—death of a loved one, contracting a dread disease, loss of a job, divorce, prison, financial ruin, bankruptcy—not only recover but come out better off than their previous stable status.

When most people look back on their successes, they realize there were a series of failures that allowed them to navigate to success,” says Jeff Stibel, the CEO of Dun & Bradstreet Credibility Corp., quoted in a 2014 book, “The Up Side of Down.” Author Megan McArdle, a columnist for Bloomberg, writes in this book about major setbacks

in personal or professional lives and why some failures inspire breakthroughs and others breakdowns.

Learning from our mistakes starts with being able to getting past denying we make mistakes. There are many examples from major business turnarounds to very personal stories that started with awareness, admitting, and even publicizing these events.

Two famous business-related turnarounds are similar in that both involve venerated companies which were slipping toward financial death and were turned around by a new CEO who sought real feedback—be it good or bad—which changed the culture of their institutions.

Ford Motor Company: Its future was sinking in 2006 as foreign automakers’ market share soared and the U. S. economy took a dive. Alan Mulally, a new executive invited by Bill Ford, Jr., came from the Boeing Company where he had led successfully through a series of near catastrophes.

According to one reporter dedicated to covering Ford, “While Toyota Motor Corporation and Honda Motor Company were booking record profits, Ford was about to announce a $12.6 billion loss—the biggest in its century-long history. Yet Ford’s most serious competition was inside the company itself. The automaker’s global divisions had

become warring factions as executives fought for supremacy in what had become one of the most cutthroat, careerist cultures in the business.”

WHAT DID MULALLY DO IN TERMS OF LEADERSHIP?

- He had everyone share metrics using a scorecard color-coded green for good, yellow for concern, and red for problems.

- And, equally importantly, he had everyone share their “report cards” weekly at a meeting whose goal was to first identify problems and second and more importantly, learn from each other so they could share knowledge and improve.

By having a data driven organization, “There’s nowhere to hide,” Mulally told the reporter, “It’s all right there for everyone to see.” Being relentless is also a characteristic of successful organizations and people. “Grit” is a term applied to those with stamina and determination. This Ford CEO had the determination to manage through the crisis, change the culture, and in the end Ford was better off by far. Ford needed “a near death experience,” to change.

By July 2014, reported Reuters, Ford’s profits had beat Wall Street expectations and set records in North America and Europe.

Alcoa: Another story of a challenged company coming back stronger after a series of bad safety experiences is Alcoa Aluminum Company, which was floundering in October 1987. The incoming CEO, Paul O’Neill, came from the U. S. Veterans Administration with a background as a computer systems analyst. Prior to that Mr. O’Neill was with the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

With each organization Mr. O’Neill developed the reputation of being inquisitive and always working on ways to improve. When given an answer by a colleague, he would always ask another penetrating question. Mr. O’Neill gave his first speech as CEO of Alcoa in a Manhattan ballroom when he was brought in to reverse the financial

misfortunes, as the company was on the skids.

Investors were nervous, since Alcoa had faltered with failed product lines.

As Charles Duhigg, a Pulitzr prize-winning reporter, describes in the Power of Habit, “But O’Neill didn’t talk about profit margins, revenue projections, or anything else that would be comforting to Wall Street ears. ‘I want to talk to you about worker safety,’ he began.

The room went silent.

‘Every year, numerous Alcoa workers are injured so badly that they miss a day of work,’ O’Neill continued. ‘Our safety record is better than the general American workforce,

especially considering that our employees work with metals that are 1500 degrees and machines that can rip a man’s arm off. But it’s not good enough. I intend to make Alcoa the safest company in America. I intend to go for zero injuries.’

The audience was bewildered. A furtive hand went up, asking about inventories. ‘I’m not certain you heard me,’ O’Neill continued. ‘If you want to understand how Alcoa is doing, you need to look at our workplace safety figures.’ For the new CEO, safety trumped profits.

Investors ran out of the room as soon as the New York based presentation finished. One sprinted to a phone and called his 20 largest clients telling them they put a crazy hippie in charge who was going to kill the company. He said later, “I ordered them to sell their stock immediately, before everyone else in the room started calling their clients and telling them the same thing. It was literally the worst piece of advice I gave in my entire career.”

The emphasis on safety made an impact. Over O’Neill’s tenure, Alcoa dropped from 1.86 lost work days to injury per 100 workers to 0.2. By 2012, the rate had fallen to 0.125.

Surprisingly, that impact extended beyond worker health. One year after O’Neill’s speech, the company’s profits hit a record high.

Focusing on that one critical metric, or what Duhigg refers to as a “keystone habit,” created a change that rippled through the whole culture. Duhigg says the focus on worker safety led to an examination of an inefficient manufacturing process—one that made for suboptimal aluminum and danger for workers. By changing the safety habits, O’Neill improved several processes in the organization.

When he retired, 13 years later, Alcoa’s annual net income was five times higher than when he started. The new approach to safety led to a change in culture, O’Neill

explained to Duhigg:

“I knew I had to transform Alcoa. But you can’t order people to change. So I decided I was going to start by focusing on one thing. If I could start disrupting the habits around one thing, it would spread throughout the entire company.”

Out of the misery caused by a lack of safety came a reborn, robust, competent company. Another “near death” experience causing great change for the good.

A personal story: Finally, a personal story gleaned from Supersurvivors: The Surprising Link Between Suffering and Success, in which Alan Lock, the first legally blind person to row across the Atlantic Ocean, relates his dream of having a military career to becoming legally blind due to genetically related macular degeneration.

He decided he was not going to give up his life and with a sighted friend spent 86 days crossing the Atlantic to raise money for a charity dedicated to supporting people who are both deaf and blind. He has raised more money by running the 243 kilometer Marathon de Sables and trekking across Antarctica to the South Pole.

Consider: West Point cadets were assessed for qualities which lead to success, and were measured by graduation rates and subsequent career achievement. Intellectual and physical abilities mattered less than having “grit,” the ability to stay the course in the face of adversity.

The characteristic of “grit” among the leaders and challenged individuals correlates best with resiliency and subsequent success.

Everyone will face challenges and have disappointments. Having the “grit” to respond over a long haul is more important than the stress itself. Stay the course, do the right thing often enough, and you will get the right result.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!